|

Wednesday, May 23, 2007 Precision Pointing with Fat FingersA new technique for touch screens could make them easier to use. By Michael Gibson

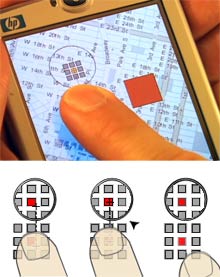

Retrieving the stylus for a personal digital assistant takes time. But for detailed work, a stylus is usually better than a finger. Microsoft researchers believe that they've found a better way to activate tiny targets, such as a name on a contact list or a street on a map. Microsoft's solution, called Shift, allows users to employ their fingertips to select pixels in a new way. First, the user presses a finger on the screen over the area of interest. Holding down her finger activates the Shift software. A detailed view of the area of interest appears nearby on the screen, in a pop-up window on top of the original image. With slight movements of her finger, the user can guide a pair of crosshairs over her desired target within the pop-up window and then make her selection by lifting her finger off the screen. "You want to give people the sensation of skill and control," says Patrick Baudisch, lead researcher on the Shift team. "We wanted it to be transparent and help people get their job done." Shift only kicks in when users touch the screen long enough--generally for about a third of a second--for it to know that they need help finding small targets with their finger. As a result, users can seamlessly move from quick finger work on detailed screens like maps and calendars to more careful interaction with their stylus when it's required. "It's important for a device to help people only when they need it," Baudisch says. "Other researchers have looked at [personal digital assistant] designs that are touch only. But as a result, you can't sketch, write, or annotate on them anymore, and you are limited to around 15 targets on the screen." On the other hand, Baudisch notes, it shouldn't be necessary to always use the stylus. "The trick is to have something that presents itself as a very simple device 90 percent of the time, yet when you need it to, it can become very powerful on demand." Researchers at the University of Maryland developed their own approach to the problem in the late 1980s. Their approach, called Offset Cursor, gave users a set of crosshairs just north of their finger to aim with every time they touched the screen. But Offset Cursor never took off. The Microsoft team points to three fundamental flaws with this early system: users are forced to guess where they should place their finger to aim the crosshairs; they are unable to access locations near the screen's edges; and they always have to select targets with the cursor offset no matter the size of the target. |

|

||||||

|

||||||

Add to Facebook

Add to Facebook

Comments